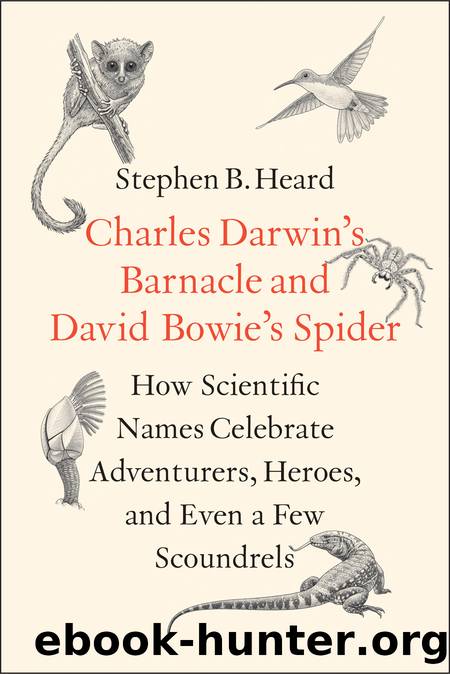

Charles Darwin's Barnacle and David Bowie's Spider by Stephen B. Heard

Author:Stephen B. Heard

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780300252699

Publisher: Yale University Press

14

Love in a Latin Name

âHow do I love thee?â asked Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and answered, âLet me count the ways.â That line, so familiar as to be perilously close to cliché, opens the 43rd of her Sonnets from the Portuguese. Barrett Browning wrote those sonnets for and about her husband, Robert Browning, turning to her professional tools as a poet to express her love. Turning to their professional tools, Pablo Picasso painted at least 60 portraits of his (first) lover, Fernande Olivier, and Richard Wagner wrote his Siegfried Idyll for his (second) wife Cosima.

That love can be recorded in poetry, or painting, or music will surprise no one. Weâre accustomed to the arts being used to explore and to record emotion. But what about science? Itâs a popular belief that thereâs no place for emotion in science, and that the scientist should therefore be coldly clinical and value detachment and objectivity above all else. It may well be true that emotion shouldnât drive the conclusions a scientist draws; but itâs certainly not true that scientists are emotionless in their work. They can show that emotion in choosing what research questions to ask, in writing or talking about what theyâve doneâor in the case of scientists who discover new species, in giving those species names. And if love is the greatest of all human emotions, itâs reassuring that poets and painters and musicians donât have a monopoly on its expression. Scientists have named new species for their daughters and their sons, their sisters and their brothers, their wives and their husbands, evenâsometimesâtheir unrequited crushes and their clandestine lovers. If insult naming shows scientists succumbing to their worst impulses, perhaps recording love in Latin names shows scientists as humans at their best.

Names in honor of children are quite common. We can begin with Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. He was a French aristocrat who became an Italian prince, but he was also a biologist and ornithologist who discovered and named a number of new bird species. (He also âdiscoveredâ and promoted a young American naturalist named John James Audubon, whose paintings of American birds later became famousâbut whose career was held back because he lacked connections with the aristocracy of American science.) In 1854, Bonaparte described a new imperial pigeon from the Philippines, naming it Ptilocolpa carola (itâs now Ducula carola). The species name, carola, is a Latinization of Charlotte, for Bonaparteâs 22-year-old daughter. Bonaparte wrote, âI dedicate it [the name] to my daughter the countess Primoli, Charlotte, herself worthy of her illustrious name,â which is touching but also a bit odd.1 Itâs odd because Bonaparte refers to his daughter as âthe countessâ and trumpets her family connections (she shared the name Charlotte with her aunt, a princess and niece of Napoleon)âyet Bonaparte was a staunch republican who decried the tendency for others to name species after royalty. In fact, four years earlier, he had named a bird of paradise Diphyllodes respublica as a statement of his republican ideals. Love,

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Coloring Books for Grown-Ups | Humor |

| Movies | Performing Arts |

| Pop Culture | Puzzles & Games |

| Radio | Sheet Music & Scores |

| Television | Trivia & Fun Facts |

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5187)

Paper Towns by Green John(5185)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4303)

Never by Ken Follett(3945)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3378)

Learning C# by Developing Games with Unity 2021 by Harrison Ferrone(3353)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3103)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3077)

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: Illustrated edition by J.K. Rowling & Newt Scamander(3024)

Will by Will Smith(2916)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2845)

How The Mind Works by Steven Pinker(2814)

Never Lie: An addictive psychological thriller by Freida McFadden(2590)

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: The Original Screenplay by J. K. Rowling(2513)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2357)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2355)

Borders by unknow(2309)

The God delusion by Richard Dawkins(2307)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2223)